[Q&A #02] Bombs vs. Bugs

Edward Snowden

Aug 2, 2021

https://edwardsnowden.substack.com/p/qa02

One of the interesting things for me about this shared space of ours is to be able to see what it is that you most enjoy—or don’t—and where your questions lie. The most common request I’ve heard is about, uh, well:

[File under “Improving Accessibility”]

Closely following that desire for what I’m going to call the occasional shorter piece in a more conversational tone, are requests for practical technical advice:

Patrick Emek writes:

“Is there any chance you might write a future article explaining in easy to understand language how one might go about removing the listening devices from mobile phones?”

stefanibus writes:

"I am a normal citizen with no intention to screw open my phone prior to using it. What shall I do after reading this article? I might need a detailed behavioral pattern. Some kind of a plan I can stick to."

Shane writes:

Would removing any of the chips remove functionality of the phone other than the spying pieces?

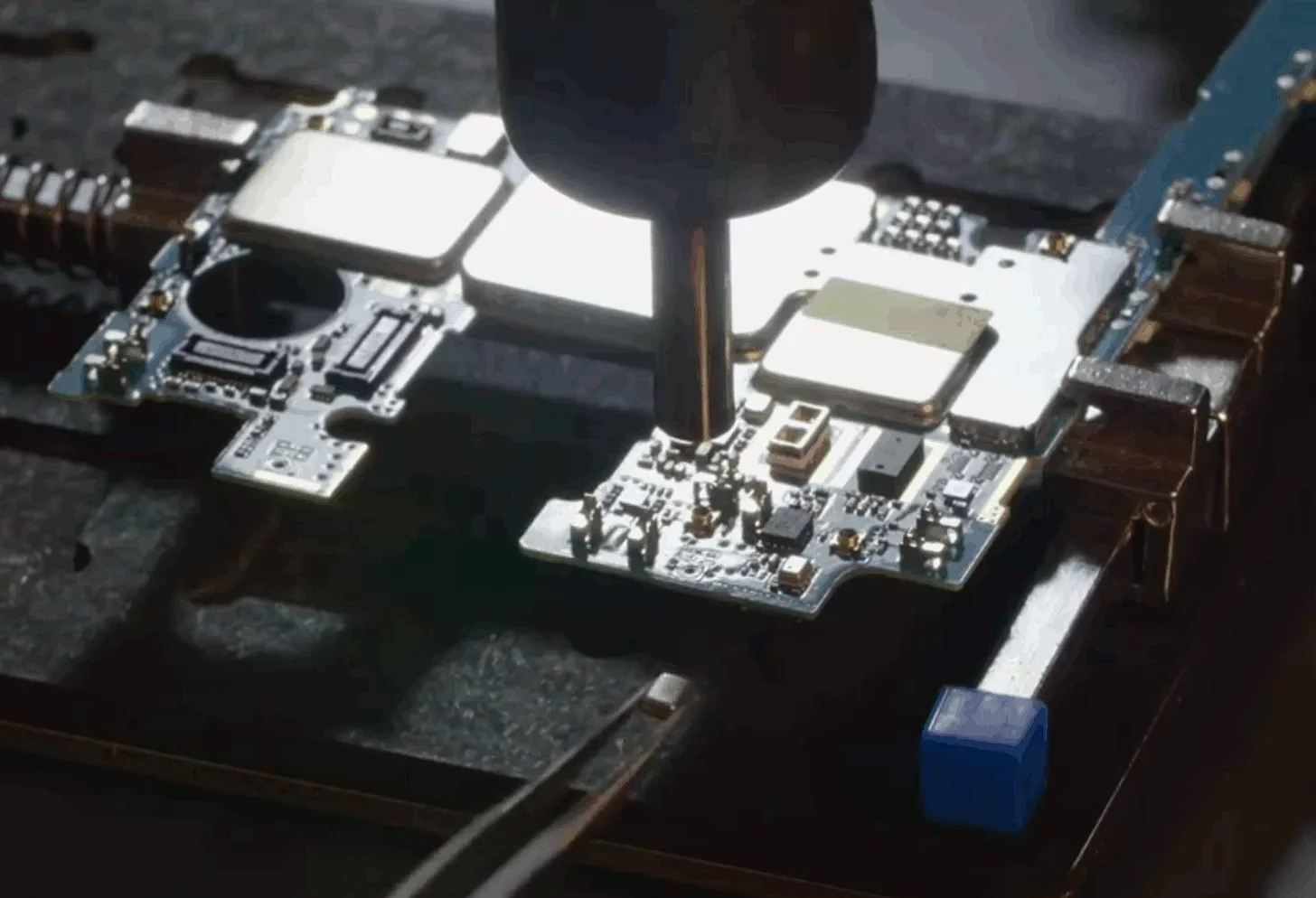

[A screencap of me removing a microphone from a phone motherboard, taken from an old promo video for the FOSS [1] app Haven [2]. (Video: [3])]

For the last eight years, I’ve tried hard to stay away from “what, specifically, should I do?” questions, because technology moves so quickly—and readers’ circumstances are so varied—that the answers tend to age off and become dangerous after just a few months, but Google will keep recommending them to people for years and years. However, I’ve recently been persuaded by the increasingly dire state of the network that the risks of bad advice are outweighed by how hard it is to develop the public understanding of even very basic technical principles. That means I’ll be taking some time in the next few months to talk about technology and my personal relationship to it, particularly how I deal with the newly hostile-by-default nature of it.

If you like, I might also be able to bring in some real experts to chat about some of the more complex problems in more depth. Let me know in the comments if audio content like that is of interest.

Addict writes:

«While I agree that they need to be stopped, I'm worried about what consequences it might have to ban code. I personally view code as a form of free speech, but I am not sure what implications it might have to ban specific forms of code.»

I struggle with this question quite a bit myself. It’s apparent to me that just as we cannot trust governments to decide the things that can and cannot be said, we should not empower them to start permitting the applications that we can write (or install). However, we also have to recognize that until your neighbors are lining up to storm the Bastille [4], we’re forced to respond to policy crises within the context of the system that currently exists.

The government already manages to (unconstitutionally) regulate speech in the United States through various means: we need look no further for examples than the Espionage Act, or the abuse of state secrecy to prevent any accountability for those involved in the CIA’s recent torture program. I’m fairly confident that you could watch any arbitrary White House Press Conference today to witness indicia of that continuing impulse applied to new controversies [5]. And as you say, outside the United States, circumstances are often similar or worse.

How, then, do we restrain the governmental impulse to reward cronies and punish inconvenient voices in the context of something as complex as exploit code? If we’re going to ensure publicly harmful activity (the insecurity industry) is impacted while exempting the publicly beneficial—defenders, researchers, and uncountable categories of benign tinkerers—we need to identify some variable that is always present in category A, but not strictly required by category B.

And we have that, here. That thing is the profit motive.

Nobody goes to work at the NSO Group to save the world. They do it to get rich. They can’t do that without the ability to sell the exploits they develop far and wide. You ban the commercial trade in exploit code, and they’re out of business.

In contrast, a researcher at the University of Michigan writing a paper on iOS exploitation or some kid on a farm trying to repair their family’s indefensibly DRM-locked John Deere tractor is not going to be deterred from doing that just because they can’t sell the result to the most recent cover model for Repressive Dictator magazine.

That’s the crucial caveat that I think many missed regarding my call for a global moratorium: it is a prohibition on the commercial trade—that is to say, specifically the for-profit exploitation of society at large, which is the raison d’etre of the insecurity industry—rather than the mere development, production, or use of exploit code. My proposal here is in fact closer to an inversion of the government’s response to Defense Distributed [6], where it sought to reflexively ban the mere transmission of information without regard to motivation, use, or consequence.

Eoan writes:

«Which is more likely to kill someone if allowed to be sold: a software exploit or a 250-kg air-dropped bomb?»

I think this misses the point. Beyond the question of “how do they know where to drop the bomb?”, there’s a more important one: “which of these is more likely to be used?”

Bombs are blunt instruments, the ultima ratio regum of a state that has exhausted its ability—or appetite—to engage in less visible forms of coercion. They are at least intended to be the very end of the kill-chain [7], the warhead-on-forehead that erases the inconvenient problem.

Software exploits, in contrast, are at the very top of that chain. They are the means by which a state decides who and where to bomb—if it even gets that far, since spying provides an unusual menu [8] of options for escalation. As I mentioned [9], a software vulnerability can be exploited repeatedly, widely, and nearly invisibly. Unlike a bomb, if an exploit generates a headline, it will most probably happen years later instead of on that evening’s news. The result is that spying is far more common than bombing, and in many ways becoming prerequisite to it.

Another little-understood property that make exploits more dangerous than bombs—and they definitely are—is that, as with the viral strain of a biological weapon, as soon as an adversary catches a sample of an exploit, they can perfectly reproduce it... and then use it themselves against anyone they want.

When you fire a rocket or drop a bomb, you don’t have to worry about the target catching it and throwing it back at you. But with exploits, every time you use it, you run the risk of losing it.

All of this is to say that while we can’t stop the sale of bombs, when the Saudis then drop that bomb on someone, we know that it happened, we often know who made it (from the markings on exploded fragments at the scene), we normally know who dropped it, and we know who it was dropped on. In the vast majority of cases involving the insecurity industry’s hacking-for-hire, not one of these details are known to us, and all of them are important in providing for the possibility of enforcing accountability for misuse.

Links:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_and_open-source_software

[2] https://guardianproject.github.io/haven/

[3] https://tube.incognet.io/watch?v=Fr0wEsISRUw

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storming_of_the_Bastille

[5] https://reason.com/2021/07/21/biden-is-trying-to-impose-online-censorship-by-proxy/

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Defense_Distributed#Legal_challenges

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kill_chain

[8] https://www.huffpost.com/entry/nsa-porn-muslims_n_4346128

[9] https://edwardsnowden.substack.com/p/ns-oh-god-how-is-this-legal

The Insecurity Industry

The greatest danger to national security has become the companies that claim to protect it

Edward Snowden

Jul 26, 2021

https://edwardsnowden.substack.com/p/ns-oh-god-how-is-this-legal

1.

The first thing I do when I get a new phone is take it apart. I don’t do this to satisfy a tinkerer’s urge, or out of political principle, but simply because it is unsafe to operate. Fixing the hardware, which is to say surgically removing the two or three tiny microphones hidden inside, is only the first step of an arduous process, and yet even after days of these DIY security improvements, my smartphone will remain the most dangerous item I possess.

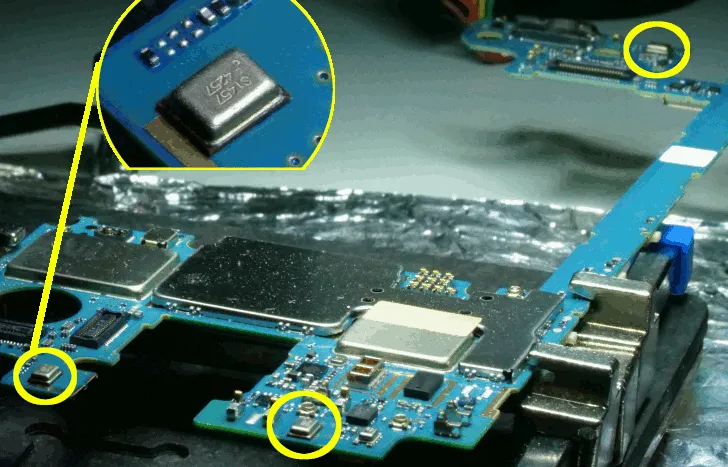

[The microphones inside my actual phone, prepped for surgery]

Prior to this week’s Pegasus Project [1], a global reporting effort by major newspapers to expose the fatal consequences of the NSO Group [2]—the new private-sector face of an out-of-control Insecurity Industry—most smartphone manufacturers along with much of the world press collectively rolled their eyes at me whenever I publicly identified a fresh-out-of-the-box iPhone as a potentially lethal threat.

Despite years of reporting that implicated the NSO Group’s for-profit hacking of phones in the deaths and detentions of journalists and human rights defenders [3]; despite years of reporting that smartphone operating systems were riddled with catastrophic security flaws [4] (a circumstance aggravated by their code having been written in aging programming languages that have long been regarded as unsafe); and despite years of reporting that even when everything works as intended, the mobile ecosystem is a dystopian hellscape of end-user monitoring [5] and outright end-user manipulation, it is still hard for many people to accept that something that feels good may not in fact be good. Over the last eight years I’ve often felt like someone trying to convince their one friend who refuses to grow up to quit smoking and cut back on the booze—meanwhile, the magazine ads still say “Nine of Ten Doctors Smoke iPhones!” and “Unsecured Mobile Browsing is Refreshing!”

In my infinite optimism, however, I can’t help but regard the arrival of the Pegasus Project [6] as a turning-point—a well-researched, exhaustively-sourced, and frankly crazy-making story about a “winged” “Trojan Horse” infection named “Pegasus” that basically turns the phone in your pocket into an all-powerful tracking device that can be turned on or off, remotely, unbeknownst to you, the pocket’s owner.

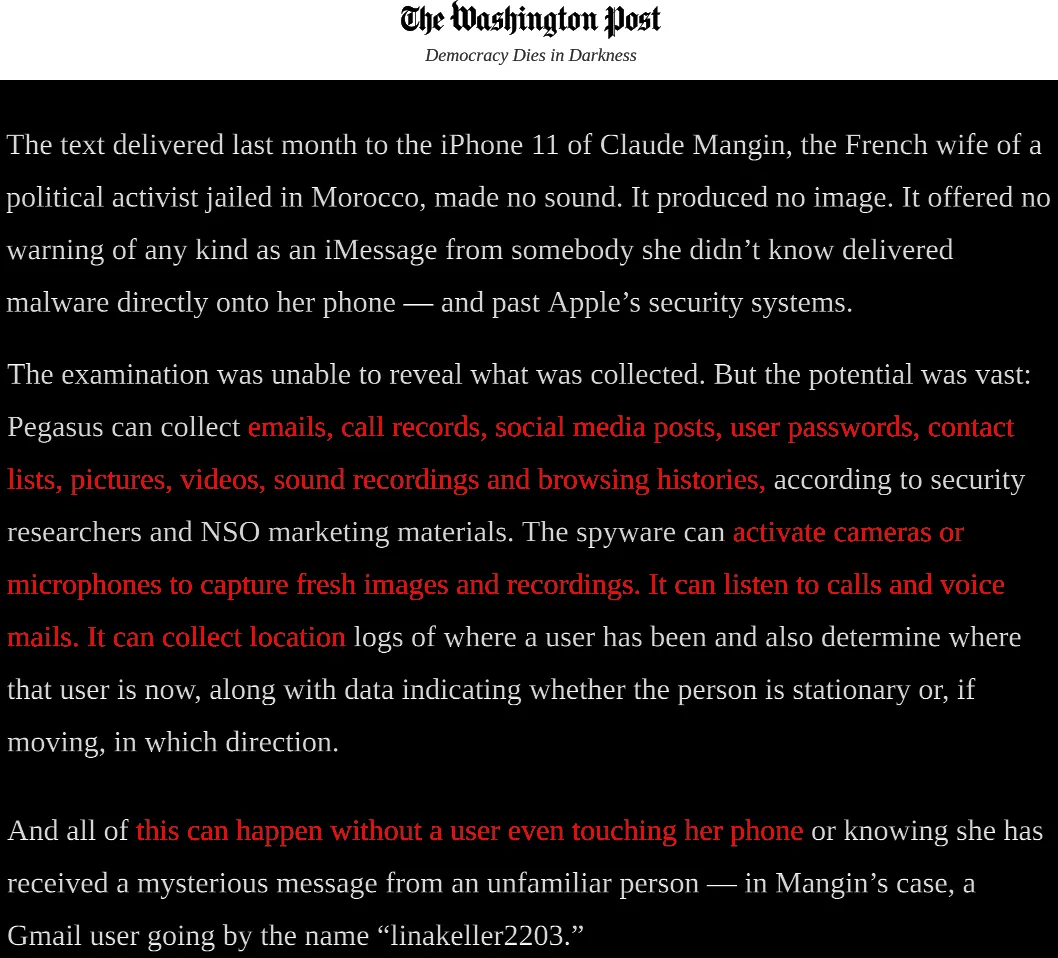

Here is how the Washington Post [7] describes it:

In short, the phone in your hand exists in a state of perpetual insecurity, open to infection by anyone willing to put money in the hand of this new Insecurity Industry. The entirety of this Industry’s business involves cooking up new kinds of infections that will bypass the very latest digital vaccines—AKA security updates—and then selling them to countries that occupy the red-hot intersection of a Venn Diagram between “desperately craves the tools of oppression” and “sorely lacks the sophistication to produce them domestically.”

An Industry like this, whose sole purpose is the production of vulnerability, should be dismantled.

Links:

[1] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/07/the-pegasus-project/

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/17/world/middleeast/israel-saudi-khashoggi-hacking-nso.html

[3] https://www.digitalviolence.org/

[5] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/23/opinion/data-internet-privacy-tracking.html

[6] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/07/the-pegasus-project/

[7] https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/07/19/apple-iphone-nso/

2.

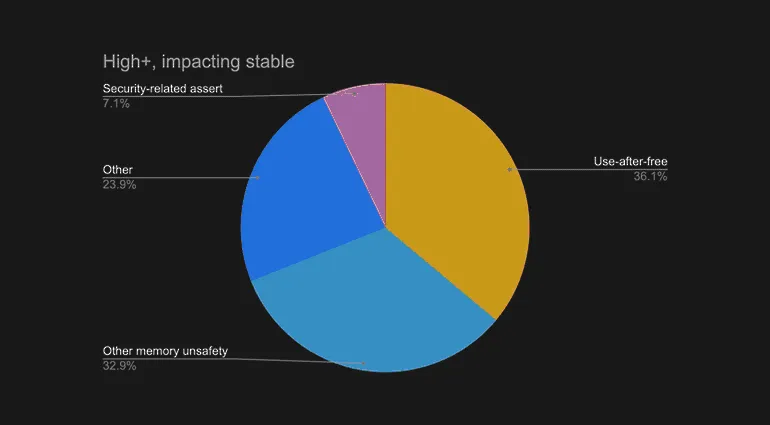

Even if we woke up tomorrow and the NSO Group and all of its private-sector ilk had been wiped out by the eruption of a particularly public-minded volcano, it wouldn’t change the fact that we’re in the midst of the greatest crisis of computer security in computer history. The people creating the software behind every device of any significance—the people who help to make Apple, Google, Microsoft, an amalgamation of miserly chipmakers who want to sell things, not fix things, and the well-intentioned Linux developers who want to fix things, not sell things—are all happy to write code in programming languages that we know [1] are unsafe, because, well, that’s what they’ve always done, and modernization requires a significant effort, not to mention significant expenditures. The vast majority of vulnerabilities that are later discovered and exploited by the Insecurity Industry are introduced, for technical reasons related to how a computer keeps track of what it’s supposed to be doing, at the exact time the code is written, which makes choosing a safer language [2] a crucial protection... and yet it’s one that few ever undertake.

[Google said 70% of serious bugs in its Chrome Browser are related to memory safety. These can be reduced by using safer programming languages.]

If you want to see change, you need to incentivize change. For example, if you want to see Microsoft have a heart attack, talk about the idea of defining legal liability for bad code in a commercial product. If you want to give Facebook nightmares, talk about the idea of making it legally liable for any and all leaks of our personal records that a jury can be persuaded were unnecessarily collected. Imagine how quickly Mark Zuckerberg would start smashing the delete key.

Where there is no liability, there is no accountability... and this brings us to the State.

Links:

[1] https://msrc-blog.microsoft.com/2019/07/18/we-need-a-safer-systems-programming-language/

[2] https://www.rust-lang.org/

3.

State-sponsored hacking has become such a regular competition that it should have its own Olympic category in Tokyo. Each country denounces the others’ efforts as a crime, while refusing to admit culpability for its own infractions. How, then, can we claim to be surprised when Jamaica shows up with its own bobsled team? Or when a private company calling itself “Jamaica” shows up and claims the same right to “cool runnings” [1] as a nation-state?

If hacking is not illegal when we do it, then it will not be illegal when they do it—and “they” is increasingly becoming the private sector. It’s a basic principle of capitalism: it’s just business. If everyone else is doing it, why not me?

This is the superficially logical reasoning that has produced pretty much every proliferation problem in the history of arms control, and the same mutually assured destruction implied by a nuclear conflict is all-but guaranteed [2] in a digital one, due to the network’s interconnectivity, and homogeneity.

Recall our earlier topic of the NSO Group’s Pegasus, which especially but not exclusively targets iPhones. While iPhones are more private by default and, occasionally, better-engineered from a security perspective than Google’s Android operating system, they also constitute a monoculture [3]: if you find a way to infect one of them, you can (probably) infect all of them, a problem exacerbated by Apple’s black-box refusal to permit customers to make any meaningful modifications to the way iOS devices operate. When you combine this monoculture and black-boxing with Apple’s nearly universal popularity among the global elite, the reasons for the NSO Group’s iPhone fixation become apparent.

Governments must come to understand that permitting—much less subsidizing—the existence of the NSO Group and its malevolent peers does not serve their interests, regardless of where the client, or the client-state, is situated along the authoritarian axis: the last President of the United States spent all of his time in office when he wasn’t playing golf tweeting from an iPhone [4], and I would wager that half of the most senior officials and their associates in every other country were reading those tweets on their iPhones (maybe on the golf course).

Whether we like it or not, adversaries and allies share a common environment, and with each passing day, we become increasingly dependent on devices that run a common code.

The idea that the great powers of our era—America, China, Russia, even Israel—are interested in, say, Azerbaijian attaining strategic parity in intelligence-gathering is, of course, profoundly mistaken. These governments have simply failed to grasp the threat, because the capability-gap hasn’t vanished—yet.

Links:

[3] https://www.macrumors.com/2021/06/04/ios-14-installation-rates-june-2021/

[4] https://www.politico.com/story/2018/05/21/trump-phone-security-risk-hackers-601903

4.

In technology as in public health, to protect anyone, we must protect everyone. The first step in this direction—at least the first digital step—must be to ban the commercial trade in intrusion software. We do not permit a market in biological infections-as-a-service, and the same must be true for digital infections. Eliminating the profit motive reduces the risks of proliferation while protecting progress, leaving room for publicly-minded research and inherently governmental work.

While removing intrusion software from the commercial market doesn’t also take it away from states, it does ensure that reckless drug dealers and sex-criminal Hollywood producers who can dig a few million out of their couch cushions won’t be able to infect any or every iPhone on the planet, endangering the latte-class’ shiny slabs of status.

Such a moratorium, however, is mere triage: it only buys us time. Following a ban, the next step is liability. It is crucial to understand that neither the scale of the NSO Group’s business, nor the consequences it has inflicted on global society, would have been possible without access to global capital from amoral firms like Novalpina Capital (Europe) and Francisco Partners (US). The slogan is simple: if companies are not divested, the owners should be arrested. The exclusive product of this industry is intentional, foreseeable harm, and these companies are witting accomplices. Further, when, a business is discovered to be engaging in such activities at the direction of a state [1], liability should move beyond more pedestrian civil and criminal codes to invoke a coordinated international response.

[Diplomacy by other means]

Links:

5.

Imagine you’re the Washington Post’s Editorial Board (first you’ll have to get rid of your spine). Imagine having your columnist murdered and responding with a whispered appeal to the architects of that murder that next time they should just fill out a bit more paperwork [1]. Frankly, the Post’s response to the NSO scandal is so embarrassingly weak that it is a scandal in itself: how many of their writers need to die for them to be persuaded that process is not a substitute for prohibition?

Saudi Arabia, using “Pegasus,” hacked the phones [2] of Jamal Khashoggi’s ex-wife, and of his fiancée, and used the information gleaned to prepare for his monstrous killing and its subsequent cover-up.

But Khashoggi is merely the most prominent of Pegasus’ victims — due to the cold-blooded and grisly nature of his murder. The NSO Group’s “product” (read: “criminal service”) has been used to spy on countless other journalists, judges, and even teachers. On opposition candidates [3], and on targets’ spouses and children, their doctors, their lawyers, and even their priests [4]. This is what people who think a ban is “too extreme” always miss: this Industry sells the opportunity to gun down reporters you don’t like at the car wash [5].

If we don’t do anything to stop the sale of this technology, it’s not just going to be 50,000 targets: It’s going to be 50 million targets, and it’s going to happen much more quickly than any of us expect.

This will be the future: a world of people too busy playing with their phones to even notice that someone else controls them.

Links:

[3] https://citizenlab.ca/2017/06/more-mexican-nso-targets/

https://edwardsnowden.substack.com/p/ns-oh-god-how-is-this-legal/comments

Answering Readers' Questions

On Truth, Conspiracy, and... Anime?

Edward Snowden

Jul 19, 2021

https://edwardsnowden.substack.com/p/qa01

Jonathan T / ChumbaRoomba ask:

«What if instead of Conspiracy enabling individuals to abdicate from the making of truth-value judgments, Conspiracy Practice and Conspiracy Theory emerge from an interwoven tapestry of narratives formed of the truth-value judgments of a multitude of individuals—and only when examined holistically in the context of the knowns and unknowns of history can we see who made good judgments based on true or false facts and who made bad ones? ...How do we sort True conspiracies from False?»

This is a great question, and one I still struggle with. To put it in my own terms: could it be that what I regard as the malevolence of conspiracy practice and the ignorance of conspiracy theory simply stems from well-meaning people adhering to, and making decisions based on, what they regard as their truth?

I’m not sure I have a decent answer. Certainly the secular world has this experience when dealing with extremist religious groups. How can an athiest tell a true believer that they are wrong, when they claim the authority of a god? Contemporary politics are, to my mind, similarly as much or more a test of faith than an examination of fact. The core problem is to identify a space where the definition of truth can be narrowed to some set of facts that can be measured, tested—verified, from the latin verificare: to make true.

Too often we forget that the unverified is, quite literally, not truly "true." It can still be reasonable, and even probable, but fact unverified is no fact at all, a circumstance made all the more difficult in a moment when the truth has become emotionalized or psychologized, and increasingly confused for what’s more accurately called “belief.”

Thomas Moller-Nielsen asks:

«I don’t quite see how the Liar’s Paradox is supposed to relate to the issue of self-censorship. As I understand it, The Liar’s Paradox involves sentences which cannot be either true or false without entailing a contradiction. (“This sentence is false”, if true, is false, and if false, it is true.) Self-censorship, on the other hand, involves refraining from publicly uttering one’s beliefs due to fear of possible negative social/political/economic/consequences. But what does the former have to do with the latter? What is logically paradoxical about failing to publicly air one’s views?»

It has been said that I'm prone to failures of elaboration. In this case, I invoked the Liar’s Paradox to describe and contextualize the role not of the writer or speaker but of the reader or listener: In a culture of self-censorship, how do we who consume news and opinion know what to believe? How can we tell when someone is being honest (or thinks they’re being honest)? Self-censorship doesn’t just prevent communicators from expressing themselves freely. It eventually erodes the trust of the public—the true “silent majority” who might not have a platform, or want a platform, from which to speak, but who rely on the voices of others to inform them.

Larsiusprime asks:

«Ed—how much do you think the current state of the internet is due to the surveillance impetus of state actors, and how much [to] private forces? Or are they inherently related? Curious which end of the dog is wagging which, in your opinion.»

Good timing on this one: today's news is full of the escapades of one of those private forces, namely the Israeli NSO Group’s sale of hacking tools to the likes Kazakhstan, Azerbaijian, Mexico, and Hungary. These tools, which were developed by the Israeli state—or more accurately those recently in the employ of the Israeli state—were sold by NSO, nominally a private company. The links between the two significantly complicate any answer. Look to this space later this week for more in-depth treatments of this issue, but for now let me just say this: while it's not easy to tell where the state ends and the private begins, it's not hard to see that it’s those whose seek to limit the expression of institutional powers—journalists and opposition candidates and human rights activists—who most often find themselves the victims of it.

Eoan asks:

«Have you seen or read the series Liar Game?»

I wondered when the anime questions would start.

I’ve been rigorously dodging questions like this for as long as I’ve been in the public eye. Occasionally, a friend asks me why.

When you’re the subject of a controversy in an environment where a significant portion of the media has greater economic incentives to titillate than to edify, even passing references to something like video games or anime will get you treated like a weirdo — despite the fact that they’re probably more popular than baseball, these days. That’s just how it is.

As a result, I’ve been pretty careful about the things I’ve said and how I’ve said them, because my every utterance was evaluated by the worst people on Earth for its utility in not only discrediting me as a person, but me as a proxy for people in favor of surveillance reform. I cared a lot about that, and so I worked hard to minimize my peculiarities — or at least the evidence of them.

Fortunately for all of us, The Peculiarities Of Edward Snowden is no longer the kind of article that gets assigned at The New Yorker anymore — except in place of something like a book review, if a writer can’t be bothered to read or understand the text — which means I have finally recovered a lost freedom.

That freedom is, in part, what has enabled me to start this newsletter, which is probably the only place where someone will be able to ask me about a wildly obscure manga like Liar Game, and I’ll be able to say, “Yeah, sure: I read it — at least through the Contraband arc.”

What a world.

Links:

A Conversation with Daniel Ellsberg

The whistleblower who started it all

Edward Snowden

Jul 14, 2021

https://edwardsnowden.substack.com/p/ellsberg1#details

For the Fourth of July, I reached out to an old friend, Daniel Ellsberg, to experiment with recording little conversations for you about big topics. Production quality will be a bit rough around the edges until I get the hang of it, but I hope you enjoy it.

The wonderful music was provided by the talented Jamie Saft (Twitter: @jamiesaft). My deepest thanks, friend.

Links:

Conspiracy: Theory and Practice

Toward a Taxonomy of Conspiracies

Edward Snowden

Jun 29, 2021

https://edwardsnowden.substack.com/p/conspiracy-pt1

I.

The greatest conspiracies are open and notorious — not theories, but practices expressed through law and policy, technology, and finance. Counterintuitively, these conspiracies are more often than not announced in public and with a modicum of pride. They’re dutifully reported in our newspapers; they’re bannered onto the covers of our magazines; updates on their progress are scrolled across our screens — all with such regularity as to render us unable to relate the banality of their methods to the rapacity of their ambitions.

The party in power wants to redraw district lines. The prime interest rate has changed. A free service has been created to host our personal files. These conspiracies order, and disorder, our lives; and yet they can’t compete for attention with digital graffiti about pedophile Satanists in the basement of a DC pizzeria.

This, in sum, is our problem: the truest conspiracies meet with the least opposition.

Or to put it another way, conspiracy practices — the methods by which true conspiracies such as gerrymandering, or the debt industry, or mass surveillance are realized — are almost always overshadowed by conspiracy theories: those malevolent falsehoods that in aggregate can erode civic confidence in the existence of anything certain or verifiable.

In my life, I’ve had enough of both the practice and the theory. In my work for the United States National Security Agency, I was involved with establishing a Top-Secret system intended to access and track the communications of every human being on the planet. And yet after I grew aware of the damage this system was causing — and after I helped to expose that true conspiracy to the press — I couldn’t help but notice that the conspiracies that garnered almost as much attention were those that were demonstrably false: I was, it was claimed, a hand-picked CIA operative sent to infiltrate and embarrass the NSA; my actions were part of an elaborate inter-agency feud. No, said others: my true masters were the Russians, the Chinese, or worse — Facebook.

[Contrary to what a surprisingly large number of people on Twitter believe, that is very much not me.]

As I found myself made vulnerable to all manner of Internet fantasy, and interrogated by journalists about my past, about my family background, and about an array of other issues both entirely personal and entirely irrelevant to the matter at hand, there were moments when I wanted to scream: “What is wrong with you people? All you want is intrigue, but an honest-to-God, globe-spanning apparatus of omnipresent surveillance riding in your pocket is not enough? You have to sauce that up?”

It took years — eight years and counting in exile — for me to realize that I was missing the point: we talk about conspiracy theories in order to avoid talking about conspiracy practices, which are often too daunting, too threatening, too total.

II.

It's my hope in this post and in posts to come to engage a broader scope of conspiracy-thinking, by examining the relationship between true and false conspiracies, and by asking difficult questions about the relationships between truth and falsehood in our public and private lives.

I'll begin by offering a fundamental proposition: namely, that to believe in any conspiracy, whether true or false, is to believe in a system or sector run not by popular consent but by an elite, acting in its own self-interest. Call this elite the Deep State, or the Swamp; call it the Illuminati, or Opus Dei, or the Jews, or merely call it the major banking institutions and the Federal Reserve — the point is, a conspiracy is an inherently anti-democratic force.

The recognition of a conspiracy — again, whether true or false — entails accepting that not only are things other than what they seem, but they are systematized, regulated, intentional, and even logical. It’s only by treating conspiracies not as “plans” or “schemes” but as mechanisms for ordering the disordered that we can hope to understand how they have so radically displaced the concepts of “rights” and “freedoms” as the fundamental signifiers of democratic citizenship.

In democracies today, what is important to an increasing many is not what rights and freedoms are recognized, but what beliefs are respected: what history, or story, undergirds their identities as citizens, and as members of religious, racial, and ethnic communities. It’s this replacement-function of false conspiracies — the way they replace unified or majoritarian histories with parochial and partisan stories — that prepares the stage for political upheaval.

Especially pernicious is the way that false conspiracies absolve their followers of engaging with the truth. Citizenship in a conspiracy-society doesn’t require evaluating a statement of proposed fact for its truth-value, and then accepting it or rejecting it accordingly, so much as it requires the complete and total rejection of all truth-value that comes from an enemy source, and the substitution of an alternative plot, narrated from elsewhere.

III.

The concept of the enemy is fundamental to conspiracy thinking — and to the various taxonomies of conspiracy itself. Jesse Walker [1], an editor at Reason and author of The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory (2013), offers the following categories of enemy-based conspiracy thinking:

“Enemy Outside,” which pertains to conspiracy theories perpetrated by or based on actors scheming against a given identity-community from outside of it

“Enemy Within,” which pertains to conspiracy theories perpetrated by or based on actors scheming against a given identity-community from inside of it

“Enemy Above,” which pertains to conspiracy theories perpetrated by or based on actors manipulating events from within the circles of power (government, military, the intelligence community, etc.)

"Enemy Below," which pertains to conspiracy theories perpetrated by or based on actors from historically disenfranchised communities seeking to overturn the social order

“Benevolent Conspiracies,” which pertains to extra-terrestrial, supernatural, or religious forces dedicated to controlling the world for humanity's benefit (similar forces from Beyond who work to the detriment of humanity Walker might categorize under “Enemy Above”)

Other forms of conspiracy-taxonomy are just a Wikipedia link away: Michael Barkun's trinary categorization [2] of Event conspiracies (e.g. false-flags), Systemic conspiracies (e.g. Freemasons), and Superconspiracy theories (e.g. New World Order), as well as his distinction between the secret acts of secret groups and the secret acts of known groups; or Murray Rothbard's binary of “shallow” and “deep” conspiracies [3] (“shallow” conspiracies begin by identifying evidence of wrongdoing and end by blaming the party that benefits; “deep” conspiracies begin by suspecting a party of wrongdoing and continue by seeking out documentary proof — or at least “documentary proof”).

I find things to admire in all of these taxonomies, but it strikes me as notable that none makes provision for truth-value. Further, I'm not sure that these or any mode of classification can adequately address the often-alternating, dependent nature of conspiracies, whereby a true conspiracy (e.g. the 9/11 hijackers) triggers a false conspiracy (e.g. 9/11 was an inside job), and a false conspiracy (e.g. Iraq has weapons of mass destruction) triggers a true conspiracy (e.g. the invasion of Iraq).

Another critique I would offer of the extant taxonomies involves a reassessment of causality, which is more properly the province of psychology and philosophy. Most of the taxonomies of conspiracy-thinking are based on the logic that most intelligence agencies use when they spread disinformation, treating falsity and fiction as levers of influence and confusion that can plunge a populace into powerlessness, making them vulnerable to new beliefs — and even new governments.

But this top-down approach fails to take into account that the predominant conspiracy theories in America today are developed from the bottom-up, plots concocted not behind the closed doors of intelligence agencies but on the open Internet by private citizens, by people.

In sum, conspiracy theories do not inculcate powerlessness, so much as they are the signs and symptoms of powerlessness itself.

This leads us to those other taxonomies, which classify conspiracies not by their content, or intent, but by the desires that cause one to subscribe to them. Note, in particular [4], the epistemic/existential/social triad of system-justification: Belief in a conspiracy is considered “epistemic” if the desire underlying the belief is to get at “the truth,” for its own sake; belief in a conspiracy is considered “existential” if the desire underlying the belief is to feel safe and secure, under another's control; while belief in a conspiracy is considered “social” if the desire underlying the belief is to develop a positive self-image, or a sense of belonging to a community.

From Outside, from Within, from Above, from Below, from Beyond...events, systems, superconspiracies...shallow and deep heuristics...these are all attempts to chart a new type of politics that is also a new type of identity, a confluence of politics and identity that imbues all aspects of contemporary life. Ultimately, the only truly honest taxonomical approach to conspiracy-thinking that I can come up with is something of an inversion: the idea that conspiracies themselves are a taxonomy, a method by which democracies especially sort themselves into parties and tribes, a typology through which people who lack definite or satisfactory narratives as citizens explain to themselves their immiseration, their disenfranchisement, their lack of power, and even their lack of will.

Links:

[1] https://reason.com/people/jesse-walker/

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Barkun

[3] https://cdn.mises.org/20_2_2.pdf

[4] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0963721417718261

https://edwardsnowden.substack.com/p/conspiracy-pt1/comments

The Most Dangerous Censorship

Invisible but present, and far from the eyes of the public

Edward Snowden

Jun 22, 2021

https://edwardsnowden.substack.com/p/on-censorship-pt-1

I.

At the height of the events in Poland, just at the time when the trade union Solidarnosc was being outlawed, I received a letter stamped NIE CENZUROWANO. What exactly did these words mean? They were probably supposed to indicate that the country from which it came was free of censorship. But it could also mean that letters not bearing this stamp were censored, a token of the selective nature of this office, which apparently mistrusts certain citizens while trusting others. It could naturally also mean that all letters bearing this stamp actually did pass through the censor's hand. At any rate, this symbolic and ambiguous stamp gives a profound insight into the nature of censorship, which on the one hand wants to establish its rightfulness, while at the same time attempting to camouflage its very existence. For, while censorship considers itself a historical necessity and an institution destined to defend public order and the ruling political party, it does not like to admit that it is there. It sees itself as a temporary evil, to be applied during a state of war. Censorship, then, is only a transitory measure which will be scrapped as soon as all those people who write letters, books, etc are politically mature and responsible, thus exonerating the State and its representatives from having to act as guardians of their citizens.

Such is the opening of Censorship/Self [1] censorship, a landmark essay by the Serbian-Yugoslav writer Danilo Kiš [2], who was born in Subotica, on the Hungarian-Yugoslav border in 1935 and died in Paris in 1989.

Published in English in an anonymous translation in 1986, Kiš's essay on censorship is something akin to a personal manifesto, and builds on the work of numerous other dissidents of the Cold War milieu who sought to elucidate a certain power-structure in the dreaded Soviet censorship system that prevented their books from being published and their films and TV shows from being made. Dissidents in closed or closing societies naturally come to understand the 16th-century wisdom of Étienne de La Boétie [3]: the State is an abstraction, which depends on citizens — individuals — to execute its will.

Kiš was intrigued by the manner of this execution. His systemization of censorship was tripartite and hierarchal: at the top was the official apparatus — the various bureaus tasked with formulating and enforcing the rules and policies. Below that official level was the publicly legible or popular level, the world of media outlets like newspapers, magazines, and publishing houses, which employ publishers and editors to police their pages. In Kiš's view, the very reason that publishers and editors can perform the tasks of censorship is because they are “not only censors,” but...publishers and editors. Their official titles give them cover in performing the work the state demands of them, which is not shaping and creating writing, but deforming and destroying it. Finally, at the bottom of Kiš's hierarchy are what he calls the “last resort”: the printers, who, “as the most responsible elements of the working classes, will simply refuse to print the incriminated text.”

Yet the apparatus of censorship doesn’t end there. There is also what I might call the “first resort,” those censors who exist below everyone, and yet above everyone too: the author who self-censors — a figure who in contemporary Internet terms might be called the “creator,” or “maker.” This figure is me — and this figure is you. It’s someone who takes the burden of censorship unto themselves, without any official censor or cover-censor commanding them. In Kiš's estimation, this figure threatens to become the ultimate vessel or incarnation of the State, a person who has internalized its oppressions and works them on themselves. According to Kiš, the more censorship happens at this level — at the Marxist level of production, or at the level of your posting on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter — the more the presence of censorship, indeed the more the very existence of censorship, is hidden from the public.

Think about it: if the suppression is happening in your own home, if you're suppressing your own speech, who will know? And how can you ever call for help?

Links:

[1] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228608534021

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Danilo_Ki%C5%A1

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discourse_on_Voluntary_Servitude

II.

The Liar's Paradox, attributed to Eubulides [1], is famous in philosophy and logic. Its classic expression is as follows: “This sentence is a lie.” How to evaluate the sentence's truthfulness? Can it be evaluated? Any attempt to do so leads to paradox.

This is the same paradox that underlies all attempts to discuss censorship with the censored, and especially self-censorship with the self-censoring. How to begin? With what? NIE CENZUROWANO: “This statement is not censored.”

Kiš, who narrowly escaped the Holocaust and whose work was eventually suppressed in Yugoslavia, wrote passionately on this struggle:

«Whichever way you look at it, censorship is the tangible manifestation of a pathological state, the symptom of a chronic illness which develops side by side with it: self-censorship. Invisible but present, far from the eyes of the public, buried deep down in the most secret parts of the spirit, it is far more efficient than [official] censorship. While both of them induce (or are induced?) by the same means — threats, fear, blackmail — this second ill camouflages, or at any rate does not denounce, the existence of any outside constraint. The fight against censorship is open and dangerous, therefore heroic, while the battle against self-censorship is anonymous, lonely and unwitnessed, and it makes its subject feel humiliated and ashamed of collaborating.

Self-censorship means reading your own text with the eyes of another person, a situation where you become your own judge, stricter and more suspicious than anyone else. You the author know what no outside censor could ever discover: your most secret, unspoken thoughts which nonetheless you feel must be obvious to others “between the lines”... Therefore, you attribute to this imaginary censor faculties which you yourself do not possess, and to the text a significance which it actually does not have. For your alter ego pursues your thoughts ad absurdum, until the dizzy end where everything is subversive, where to tread is dangerous and condemnable.»

“Lonely and unwitnessed,” “dangerous and condemnable” — Kiš's perfect and tragic adjectives — describe how many people feel today, when confronted with the internet's many opportunities for self-presentation, and equally many opportunities for self-destruction. Under the pitiless eye of mass surveillance, which funnels the most tentative keystroke into our permanent records, we begin to surveil ourselves.

Unlike in Kiš's milieu, or in contemporary North Korea, or Saudi Arabia, the coercive apparatus doesn't have to be the secret police knocking at the door. For fear of losing a job, or of losing an admission to school, or of losing the right to live in the country of your birth, or merely of social ostracism, many of today's best minds in so-called free, democratic states have stopped trying to say what they think and feel and have fallen silent. That, or they adopt the party-line of whatever party they would like to be invited to — whatever party their livelihoods depend on.

Such is the trickle-down effect of the institutional exploitation of the internet, of corporate algorithms that thrive on controversy and division: the degradation of the soul as a source of profit — and power.

Links:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eubulides

https://edwardsnowden.substack.com/p/on-censorship-pt-1/comments

Lifting the mask

On liberty, on privacy, on Substack

Edward Snowden

Jun 15, 2021

https://edwardsnowden.substack.com/p/lifting-the-mask

1.

Eight years ago, my life began.

I was a climbing careerist in the American Intelligence Community, a former CIA officer and NSA contractor, until I discovered that my work — and the work of my generation — had, in secret, been turned toward the construction of history’s first truly global system of mass surveillance: a machine dedicated to building perfect and permanent records of our private lives.

I quietly showed documents detailing the full scope of this new architecture of oppression to my colleagues, who were first alarmed, and then filled with a sense of resignation: what can you do?

And so it was eight years ago this week that I left my partner, my family, and my country behind to reveal evidence of this malfeasance to journalists I'd never met but had to trust.

As part of this process, I also revealed my identity.

This was the moment:

«Nothing could have prepared me for the moment when [Laura Poitras] pointed her camera at me, sprawled out on my unmade bed in a cramped, messy room that I hadn’t left for the past ten days. I think everybody has had this kind of experience: the more conscious you are of being recorded, the more self-conscious you become. Merely the awareness that there is, or might be, somebody pressing record on their smartphone and pointing it at you can cause awkwardness, even if that somebody is a friend. [...] In a situation that was already high-intensity, I stiffened. The red light of Laura’s camera, like a sniper’s sight, kept reminding me that at any moment the door might be smashed in and I’d be dragged off forever. And whenever I wasn’t having that thought, I kept thinking about how this footage was going to look when it was played back in court. I realized there were so many things I should have done, like putting on nicer clothes and shaving. Room-service plates and trash had accumulated throughout the room. There were noodle containers and half-eaten burgers, piles of dirty laundry and damp towels on the floor. It was a surreal dynamic. Not only had I never met any filmmakers before being filmed by one, I had never met any journalists before serving as their source. The first time I ever spoke aloud to anyone about the US government’s system of mass surveillance, I was speaking to everyone in the world with an Internet connection. In the end, though, regardless of how rumpled I looked and stilted I sounded, Laura’s filming was indispensable, because it showed the world exactly what happened in that hotel room in a way that newsprint never could.»

That was how I described how I felt in my memoir Permanent Record. Today, when I re-read that passage, and when I replay that old clip, I have a curious sense of distance: it's me, but also it's not. I still stand by the words, yet I can't help but acknowledge that I'm always standing at a different remove, contemplating the past from a new perspective, determined by all that has changed in the time that's elapsed. Between the clip and the memoir, my girlfriend Lindsay and I were reunited and married. Between the memoir and the present, we became parents to a son. Between that child and the writing of this sentence, I developed a new appreciation for time.

Though my relationship to time fluctuates, the gravamen of my disclosures remains constant. In the past eight years, the depredations of surveillance have merely become more entrenched, with the capabilities that used to be the province of governments now in the hands of private companies, too, which employ them to track and tether us and attenuate our freedoms. This enduring danger, this compounding danger, is one of the reasons I've decided to lift my voice again — adding a new page to my "permanent record"...one to which I hope you subscribe.

2.

Since 2013, it feels as though the world has accelerated, when really only the rate of opinion has — through the sheer speed and volume of bite-sized algorithmically "curated" social media. On Facebook, and especially on Twitter, plots and characters appear and vanish in moments, imparting emotions, but never lessons, because who has time for those? The only thing that most of us manage to take away from social media, besides the occasional chuckle, is an updated roster of villains — the daily roll-call of transgressors and transgressions.

This is the reality of the fully commercialized mainstream internet: our exposure to an indigestible mass of shortest-form opinions that are purposefully selected by algorithms to agitate us on platforms that are designed to record and memorialize our most agitated, reflexive responses. These responses are, in turn, elevated in proportion to their controversy to the attention — and prejudice — of the crowd. In the resulting zero-sum blood sport that public reputation requires, combatants are incentivized to occupy the most conventionally defensible positions, which reduces all politics to ideology and splinters the polis into squabbling tribes. The products of the irreconcilable differences this process produces are nothing more than well-divided "audiences," made available to the influence of advertisers, and all that it cost us was the very foundation of civil society: tolerance.

For this reason, I'd like to do my part in encouraging a return to longer forms of thinking and writing, which provide more room for nuance and more opportunity for establishing consensus or, at the very least, respecting a diversity of perspective and, you know, science.

I want to revive the original spirit of the older, pre-commercial internet, with its bulletin boards, newsgroups, and blogs — if not in form, then in function.

The utopianism of these blogs might seem as quaint today as the sites' graphics (and glamorous MIDI audio), but whatever those outlets lacked in sophisticated design, they more than made up for in curiosity and intelligence and in their fostering of originality and experimentation. They were, when it comes down to it, not curated and templated "platforms" so much as direct expressions of the creative primacy of the individual.

One history of the Internet — and I'd argue a rather significant one — is the history of the individual's disempowerment, as governments and businesses both sought to monitor and profit from what had fundamentally been a user-to-user or peer-to-peer relationship. The result was the centralization and consolidation of the Internet — the true y2k tragedy. This tragedy unfolded in stages, a gradual infringement of rights: users had to first be made transparent to their internet service providers, and then they were made transparent to the internet services they used, and finally they were made transparent to one another. The intimate linking of users' online personas with their offline legal identity was an iniquitous squandering of liberty and technology that has resulted in today's atmosphere of accountability for the citizen and impunity for the state. Gone were the days of self-reinvention, imagination, and flexibility, and a new era emerged — a new eternal era — where our pasts were held against us. Forever.

Everything we do now lasts forever... The Internet's synonymizing of digital presence and physical existence ensures fidelity to memory, identitarian consistency, and ideological conformity. Be honest: if one of your opinions provokes the hordes on social media, you're less likely to ditch your account and start a new one than you are to apologize and grovel, or dig in and harden yourself ideologically. Neither of those "solutions" is one that fosters change, or intellectual and emotional growth.

The forced identicality of online and offline lives, and the permanency of the Internet's record, augur against forgiveness, and advise against all mercy. Technological omniscience, and the ease of accessibility, promulgate a climate of censorship that in the so-called free world instantiates as self-censorship: people are afraid to speak and so they speak the party's words... or people are afraid to speak and so they speak no words at all...

Even the most ardent practitioners of cancel culture — which I've always read as an imperative: Cancel culture! — must admit that cancellation is a form of surveillance borne of the same technological capacities used to oppress the vulnerable by patriarchal, racist, and downright unkind governments the world over. The intents and outcomes might be different — cancelled people are not sent to camps — but the modus is the same: a constant monitoring, and a rush to judgment.

3.

If this past year-and-change has taught us anything, it's how interconnected we all are — a bat coughs and the world gets sick. Vaccines aside, our greatest weapon for defeating Covid-19 has been the mask, an accessory I'd formerly appreciated only a symbol: masks make secret, masks hide, masks cover, in protests as in pandemics.

The social value of the mask has been made clear: they're not deceptive so much as protective, of ourselves and of others too. Masking is a mutual responsibility, a symbol of common identity founded in a common hope. This is the very same rhetoric I've always employed about the use of technological masks: about the use of Tor networks, virtual private networks, encryption keys, and allied technologies that protect our identities online. Over the past eight years, the number of people — of organizers, protestors, journalists, and regular people — who've adopted these masks has been heartening, but then so too has been the courage of those who speak unmasked, in situations where their speech demands the authentication of experience. As with so-called public health, so with the health of the body politic: to drop the mask requires confidence in one's fellow citizens, and in the system in general. From the blue checks to the red pills, we all want to be free to speak as ourselves, and to be recorded as ourselves, without fear of persecution, and we all want to be able to decide what that freedom means, to ourselves and to our communities, however defined. My family back home in the States, along with many of my friends in the States and in Europe, are lucky enough to now be going around unmasked, but millions — mostly in the world's poorer countries — have no such privilege. It's here that the analogy with speech freedoms comes into starkest relief: until the air is clear for all, it's clear for none.

4.

For the past eight years, I've spoken out in defense of speech freedoms on various platforms, but none has been a home. I've been edited by editors, moderated by moderators, crammed into newspaper and magazine columns next to the ads for fancy wristwatches; I've had my thoughts contorted by character-limitations and tripped-up by threads, even before they were taken out of context and misinterpreted, accidentally and willfully. Platforms should ensure a writer has full control over, and full ownership of, their intellectual property, so I'm glad to help give this one a fighting chance.

Readers of this column should expect weekly posts dealing with civil liberties and technology, in addition to commentary on the worlds of whistleblowing and leaking, a series on false conspiracies (QAnon) v. true conspiracies (debt), news roundups, and various reviews and how-tos, for good measure. Subscribers will have access to audio versions of many of the pieces, as well as to a series of podcasts, featuring conversations between myself and friends and allies and occasionally, yes — in the spirit of this space — even some folks I disagree with.

https://edwardsnowden.substack.com/p/lifting-the-mask/comments